Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Clinical

Follow this topic

Conference call: Antibiotic resistance strategy

In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

The recent RPS Science and Research Summit addressed several major issues including antibiotic resistance, artificial intelligence, personalised medicine and the future of life sciences and healthcare in the UK

Speakers

Headliners included:

• Professor Dame Sally Davies, chief medical officer for England

• Sir Andrew Dillon, chief executive of NICE

• Professor Sir Michael Rawlins, chairman of the MHRA

• Dr Diane Ashiru-Oredope, pharmacist lead for antimicrobial resistance and stewardship and HCAI at Public Health England

• Professor Chris Dowson, School of Life Sciences, Warwick University

• Mohammed Hussain, senior clinical lead for live services at NHS Digital

Professor Dame Sally Davies pulled no punches in her keynote address on the UK’s antimicrobial resistance (AMR) strategy, assuring delegates that pharmacists are “a key part of our clinical workforce and only by working together will we get this right”.

Citing the Government’s target to reduce both antimicrobial use in humans by 15 per cent by 2024 and the number of drug-resistant infections in humans by 10 per cent by 2025, she said: “We have a 20-year vision and a five-year plan, but now we have to make it happen.”

Along with raising public awareness to encourage self care and reduce expectations of antibiotics as a key continuing role for pharmacy, Dame Sally said that her ideal would be that “the GP writes the prescription and tells the patient to go along to their pharmacist to decide whether they really need it”. This could be done by “working with prescribers to review [antibiotics] that are inappropriate through evidence-based, system-wide interventions”.

However, Professor Alison Holmes, director of the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit in healthcare associated infections (HCAI) and antimicrobial resistance, stressed that more needs to be done about optimising use.

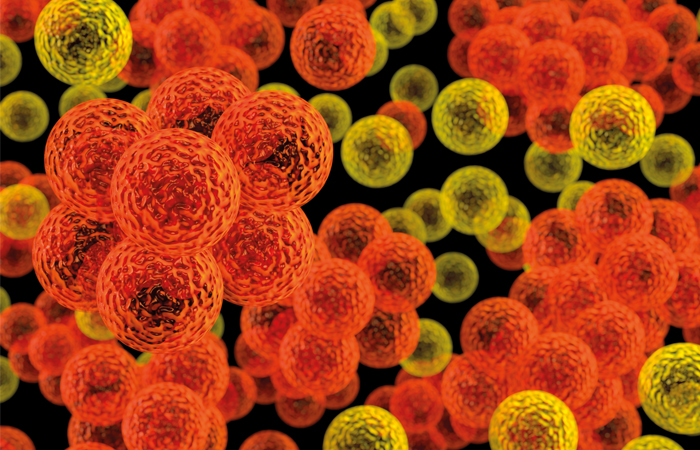

Addressing the clinical implications of AMR, she warned that 10 million deaths per year from AMR are predicted globally by 2025, and that “healthcare is generating most of this problem”. The solution, she said, is “local, regional and global stewardship”.

“Humans are the perfect biological systems to transmit AMR and we need to redesign our healthcare systems to address this. For example, up to 60 per cent of patients receive antibiotics, but up to 50 per cent of the antimicrobials in hospital may be inappropriate [and] in the UK 23 per cent [of antimicrobials] are needed for hospital acquired infections.

“There is a critical role for pharmacists to bridge healthcare teams and shift behaviours in hospitals but also in leadership in nontraditional roles such as directors of infection prevention, for example, by integrating into AMR stewardship.”

“New antibiotics need to be put away like a fire extinguisher and only used when you need them”

Positive effect

Expanding on the antibiotic stewardship role of community pharmacy, Dr Diane Ashiru- Oredope, pharmacist lead for antimicrobial resistance and stewardship and HCAI at Public Health England, said her research shows the “positive effect” that interactions with community pharmacy can have on patients.

“Thirty-eight per cent of patients expect to get an antibiotic from their GP or walk-in centre when they have a cough, flu or throat, ear, sinus or chest infection”, she said, “so reducing inappropriate prescribing is key.”

Mentioning the TARGET antibiotic toolkit, she said that when the community pharmacy resource was used to train the whole pharmacy team in a randomised controlled trial in 182 community pharmacies in the south west of the country, it led to fewer referrals to the GP for sinusitis, middle ear infections and cough.

For Dr Ryan Hamilton, advanced specialist antimicrobial pharmacist at University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust, another part of the solution is about engaging with the next generation. “Antibiotics are one of the only medicines that the more we use them, the less effective they become. This is a really important message to get across to young people,” he said.

“The evidence tells us that engaging children and young people works to improve their knowledge about AMR and your reward is when you see the penny drop. Within pharmacy practice that means engaging with public health campaigns, self-care promotion and medicines optimisation. If you can change that knowledge in a child, they bring that back home to the parents, then the whole family.”

“There is a role for pharmacists to enable the supply of digital therapeutics”

Problem pipeline

The immense efforts being made with stewardship don’t alter the fact that problems still persist at the business end of the drug pipeline.

Professor Chris Dowson from the School of Life Sciences at Warwick University pointed out that while there are around 190 new anti-cancer drugs waiting to come in, there are few new antimicrobials out there because there is considered to be little commercial potential with antimicrobials (AMs).

New AM drugs need to be put away like a fire extinguisher and only used when you need them – but drug companies don’t make any money out of drugs not being used, he said.

“You only start to make any money off-patent and that is problematic these days. When it is going to cost a billion dollars to make something and you are given a billion dollars in incentives, that is not really an incentive when you can make a cancer drug instead that will return you up to 33 times on your investment.”

His solution is to involve companies and academics to push these early stage discoveries, “but to get it to happen fast enough it needs to be development, not for profit – but that needs backing from international governments to make it happen”.

Finding solutions

Looking ahead for solutions was also the topic of a panel discussion. MHRA chair Professor Sir Michael Rawlings acknowledged that “the cost of drug development has become outrageous”. We should be looking at where the money goes and whether regulators like me can strip some of the nonsense out of that, he said.

One way to address this is to better predict the success – and, therefore, value – of new drugs, but as NICE chief executive Sir Andrew Dillon explained: “NICE can only use the data available and make the best decision we can about the value [the product] brings, but all these judgements are about sharing risk. The further upstream you go with developing a product, the more of a risk you take.

“However, the quicker you get the product to the patients, the better. So the more the data can help telescope that period and help us make a judgement, the better,” he said.

Include academia

Like Professor Dowson, Professor Chas Bountra, provice chancellor for innovation at the University of Oxford, says academia must be included. “I am an absolute believer that academia has to work with the NHS and industry intimately, because industry can’t do it on its own,” he said.

“Our problem has been developing very specific molecules that address specific issues, but we then can’t do anything else with them and some of them don’t even work.

“The people who will really change medicines next are computational scientists and mathematicians, but we are all just scientists and what is important is how we come together to focus on addressing global problems with disruptive technologies. We are on the cusp of revolution and I am particularly optimistic that using AI can help this, but we should look less at making money from drugs.”

Artificial intelligence

Professor Dowson is also a proponent of artificial intelligence (AI) to tackle AMR. “The antibiotic development void started in the 1980s after pharma companies sacked all the clever chemists and used machines to make compounds that permeated into human cells,” he said.

But these wouldn’t work for bacteria, so since then people have been fishing in a pond where they are not going to find the fish they want. “We still don’t have a good understanding of how drugs get into bugs, but AI can start to fix that.”

Mohammed Hussain, senior clinical lead for live services at NHS Digital, warned that AI “is not necessarily going to make things better” in healthcare and listed hurdles to look out for. Because AI is designed by humans it has all the associated flaws and is only as good as the databases it has been trained on, he said.

“We also need to learn a new set of languages to be able to communicate with AI. And who’s the regulator of AI in healthcare? Who is liable when it goes wrong? Then there is the privacy issue: nothing is unhackable, so who is accessing your information?

“There is a need for transparency on AI processing – patients need to know when and where AI is being used and where it isn’t – and we need to encourage dialogue between patients and professionals about what expectations of care should be and when AI should be used.”

Managing expectations was also on the agenda for Matthew Bonam, director of intelligent pharmaceuticals at AstraZeneca. Discussing the use of digital therapeutics for personalised medicine, he said that, “because we have far greater potential to do even more with technology, payers and patients are demanding more from therapy and this is driving a massive level of investment. Funding for digital health start-ups exceeded $9.5bn in 2018 – up 32 per cent on the previous year.”

This opens up opportunities for community pharmacy as well. But caution is needed. “Only 300 out of 300,000 health apps are approved as medical devices, so be very careful what you use or recommend to patients,” he warned.

“There is a role for pharmacists to enable the supply of digital therapeutics and support patients to use them to engage in self-care and self-management. While there is no Swiss Army knife of a solution that will deliver everything someone needs, it is about how what you do fits into the wider healthcare ecosystem.”